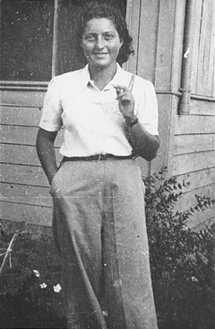

Hannah Senesh (Szenes)

(1921 - 1944)

Hannah Senesh, diarist, poet, playwright and parachutist in the Jewish resistance under the British Armed Forces during World War II was born and died in Budapest Hungary.

Considered a symbol of courage during the Holocaust, her life has been eulogized as a ‘lesson in courage.’ Hannah Senesh is one of seven parachutists from a group of thirty-two who died. She is the only one whose fate after capture is attested to with any clarity.

Now part of the popular heritage of Israel, the diary and letters of Hannah Senesh provide a primary source of information for Jewish life in Budapest during the rise of Nazism in Europe and in the work of early Zionists in Palestine. Her literary work also includes several poems, most notably, “Blessed is the Match,” and two plays, “The Violin” and “Bella gerunt alii, tu felix Austria nube.” Senesh won even greater renown after suffering torture and death for her role as a parachutist in a l944 Hagana campaign to assist Jews in Nazi-occupied Hungary.

*

Hannah was born in l921, in Budapest. The daughter of a well-known playwright and journalist Bela Senesh and his wife Katherine, Hannah was raised and educated in Budapest. Assimilated, middle-class Jews, Hannah's parents were not observant. Hannah, therefore, learned little of Judaism during her childhood. She enjoyed a comfortable standard of living in Jewish-Hungarian upper-class society, despite the death of her father in l927 when she was six. She continued to live with her mother and brother.

When she was ten years old, the tall, blue-eyed girl with brown, curly hair flowing about her elongated face, entered a private Protestant girls' high school. The school had recently begun to admit Catholics and Jews. Catholic youngsters paid double the normal tuition; Jews, triple. Nonetheless, Hannah's mother never considered sending her daughter to the Jewish high school. The girl inherited her father’s literary talent and began to excel in school at an early age, writing plays for school productions, tutoring her peers, and winning a scholarship that defrayed the inflated tuition for Jewish students.

In her first year, Hannah received excellent grades. But, her mother complained to the principal about the discrimination practiced against her daughter despite her academic success. The principal showed some flexibility; he lowered Hannah's tuition so that it equaled that paid by the Catholics. One instructor at the school was the chief rabbi of Budapest, Imre Benoschofsky, who was a great scholar and a zealous Zionist. His influence was great on Hannah's burgeoning interest in Judaism and Zionism.

She began a diary at the age of thirteen - recording her travels, relationships, day-to-day life, and desire to become a professional writer. As anti-Semitism increased in Europe, Hannah, now seventeen, was deposed from an elected post as president of her school’s literary society.

Official anti-Semitism grew in Hungary. Anti-Jewish legislation was passed. Hannah was informed that she could not take office. She was told that a Jew could not hold the presidency. What should she do, fight or hold her peace?

"You have to be someone exceptional to fight anti-Semitism...," she confided to her diary. "Only now am I beginning to see what it really means to be a Jew in a Christian society, but I don't mind at all…we have to struggle. Because it is more difficult for us to reach our goal we must develop outstanding qualities. Had I been born a Christian, every profession would be open to me."

Hannah thought about converting to Christianity in order to be able to take office. Rather than convert, however, she decided to sever her connection with the literary society. She was a determined person who stuck to her beliefs.

Hannah joined Maccabea, the most established Zionist student organization in Hungary. Toward the end of October 1938, she wrote in her diary: "I've become a Zionist. This word stands for a tremendous number of things. To me it means, in short, that I now consciously and strongly feel I am a Jew, and am proud of it. My primary aim is to go to Palestine, to work for it." Hannah's teachers tried unsuccessfully to dissuade her from leaving for Palestine.

Graduating at the top of her class in March 1939, she could easily have entered the university. Instead, she applied for a place at the Girls' Agricultural School at Nahalal in Palestine. Her interests soon turned to Zionist appeals for Jewish immigration to Palestine. Though raised in a secular household, Senesh yearned to join Jewish pioneers in Palestine. She resolved at age seventeen to learn Hebrew, and wrote: “it is the true language, and the most beautiful; in it is the spirit of our people”. She resolved to leave for Palestine upon her high school graduation: “What I love is the opportunity to create an outstanding and beautiful Jewish State.” Increasing anti-Semitism, news of her suffering people and the besieged country of Israel inspired her with dedication, with recognition of her nationality. She was deeply imbued with the Zionist ideal.

Hannah departed for Palestine shortly after the outbreak of war in Europe, before the formalization of legislation restricting economic and cultural opportunities for Hungarian Jews. Reaching Nahalal that September (where she was to spend two years), in her first letter to her mother, she wrote: "I am home .... This is where my life's ambition -I might even say my vocation - binds me, because I would like to feel that by being here I am fulfilling a mission, not just vegetating… this fulfillment of a mission."

In 1941, Senesh joined both Kibbutz Sdot Yam, was there for two years. She encountered the rigors of farming and authored her most passionate poetry. She also wrote a semi-autobiographical play about the sacrifices made by a young artist after joining a collective. Her diary chronicles wartime Palestine, detailing the influx of refugees under the British Mandate, the report from Europe and hardships experienced by the kibbutz members.

Concern for the fate of fellow Jews after Jewish immigration to Palestine was curtailed, and awareness of the mounting persecution in Europe, Palestinian Jews proposed the active engagement of a Jewish force to be allied with the British. In l943, the British allowed a limited number of Palestinian Jewish volunteers to cross behind enemy lines in occupied Europe.

By 1942, Hannah Senesh was eager to enlist in the Palmach, the commando wing of the Haganah. She also thought of returning to Hungary to help organize youth emigration. She was determined to liberate her mother from the hardships long discussed in their correspondence. Hannah Senesh enlisted with the resistance, joined the Women’s auxiliary Air Force along with several other young Jewish women. She enlisted in the British army in 1943. Their male counterparts joined the Pioneer Corps.

She wrote: “I must go to Hungary, be there at this time … and bring my mother out.” The day before she left Israel on her mission, Hannah visited her beloved brother who had just arrived from the Diaspora.

Hannah took the code name ‘Hagar” for her mission and after entrusting her poems to a friend at the kibbutz, she departed for intelligence training in Cairo. In January 1944, Hannah began training in Egypt as a paratrooper who would operate behind enemy lines. She was the first woman volunteer in the parachutist group. To her comrades she asserted: "We are the only ones who can possibly help, we don't have the right to think of our own safety; we don't have the right to hesitate .... It's better to die and free our conscience than to return with the knowledge that we didn't even try."

On the 11th March, 1944, she flew to Italy; on the 13th she parachuted to the land of the Partisans, to the former Yugoslavia where she successfully crossed the Hungarian border with the aid of a partisan group, only to be denounced the following day by an informer and taken to a Gestapo prison in Budapest. While in prison, she found an ingenious way of communicating with prisoners whose cell windows faced hers: she cut out large letters and placed them, one after the other, in her window to form words.

A comrade wrote about her: "Her behavior before members of the Gestapo and SS was quite remarkable. She constantly stood up to them, warning them plainly of the bitter fate they would suffer after their defeat. Curiously, these wild animals, in whom every spark of humanity had been extinguished, felt awed in the presence of this refined, fearless young girl."

This observation notwithstanding, both the Gestapo and Hungarian officers brutally tortured Senesh. They demanded her radio code; she refused. They threatened to torture her mother in front of her eyes, then kill her. She still would not buckle. Her mother, whom they had also imprisoned, was, in the end, released rather than tortured.

A "trial" was held on October 28, and Hannah Senesh was executed by a firing squad ten days later. Eyewitnesses from among her prison mates testified to her bravery. Hannah's last note to her mother, written in her prison cell, just prior to her execution, November 8, 1944 were:

Dearest Mother, I don't know what to say - only this:

a million thanks,

and forgive me, if you can.

You know well why words aren't necessary.

Her final words to her comrades were:

…Continue the struggle till the end

until the day of liberty comes

the day of victory for our people."

Her remains, along with those of six other fellow paratroopers who also died, were brought to Israel in 1950. They are buried together in the Israeli National Military Cemetery on Mount Herzl in Jerusalem.

Hannah Senesh’s diary and poems were published in Hebrew in 1945. They have been translated and published in other languages including Hungarian. The last poem she wrote in prison in Budapest was:

..death, I feel, is very near.

I could have been twenty-three next July;

I gambled on what mattered most,

The dice were cast.

I lost.

Nearly every Israeli can recite from memory Senesh's poem "Blessed is the Match" :

Blessed is the match consumed in kindling flame.

Blessed is the flame that burns in the secret fastness of the heart.

*

On November 5, 1993 Hannah Senesh's family in Israel received a copy of a Hungarian military court's verdict exonerating her of the treason charges for which she was executed. Israel's then Prime Minister, the late Yitzhak Rabin, attending the Tel Aviv ceremony where the document was turned over to the family, noted that for Hannah Senesh, "there is little use for the new verdict. Nor does it offer much comfort to her family. But historic justice is also a value and the new verdict...represents a measure of reason triumphing over evil."

Hannah Senesh remains an inspiration to young writers; her work ensures her place as a national heroine.

*

Several monuments to Hannah Senesh have been erected throughout Israel. Numerous streets, a forest, settlements and a species of flower were given her name. A museum, established by the Hannah Senesh Legacy Foundation, was built at her former home in Kibbutz Sdot Yam.

Courtesy of: